STOP BETTING THE HOUSE: WHY INSIDERS ARE MISREADING THE ODDS

If you have spent five minutes at a political fundraiser lately, you have heard the line.

A consultant leans in, swirls his drink and whispers that the polls are tight, but the betting markets have their candidate at 60 percent. He claims they're in the driver's seat.

It sounds sophisticated. It sounds like they have a secret decoder ring for the electorate. It is mostly nonsense.

Over the last year, I have watched seasoned political pros and journalists make a rookie mistake. People who count votes in their sleep are taking two completely different tools -polls and prediction markets - and pretending they measure the same thing.

They don't. And confusing them is how you get burned.

Polls Measure Opinion. Markets Measure Pain.

Anyone who has worked on a real campaign understands the bounds. A poll is a snapshot. It captures the opinion of a defined group of people at a moment in time, using transparent methods with known limits and a published margin of error.

Question wording, turnout models, and timing all matter. The goal is not forecasting. It is to anchor opinion to a moment. That is why pollsters use language like "if the election were held today."

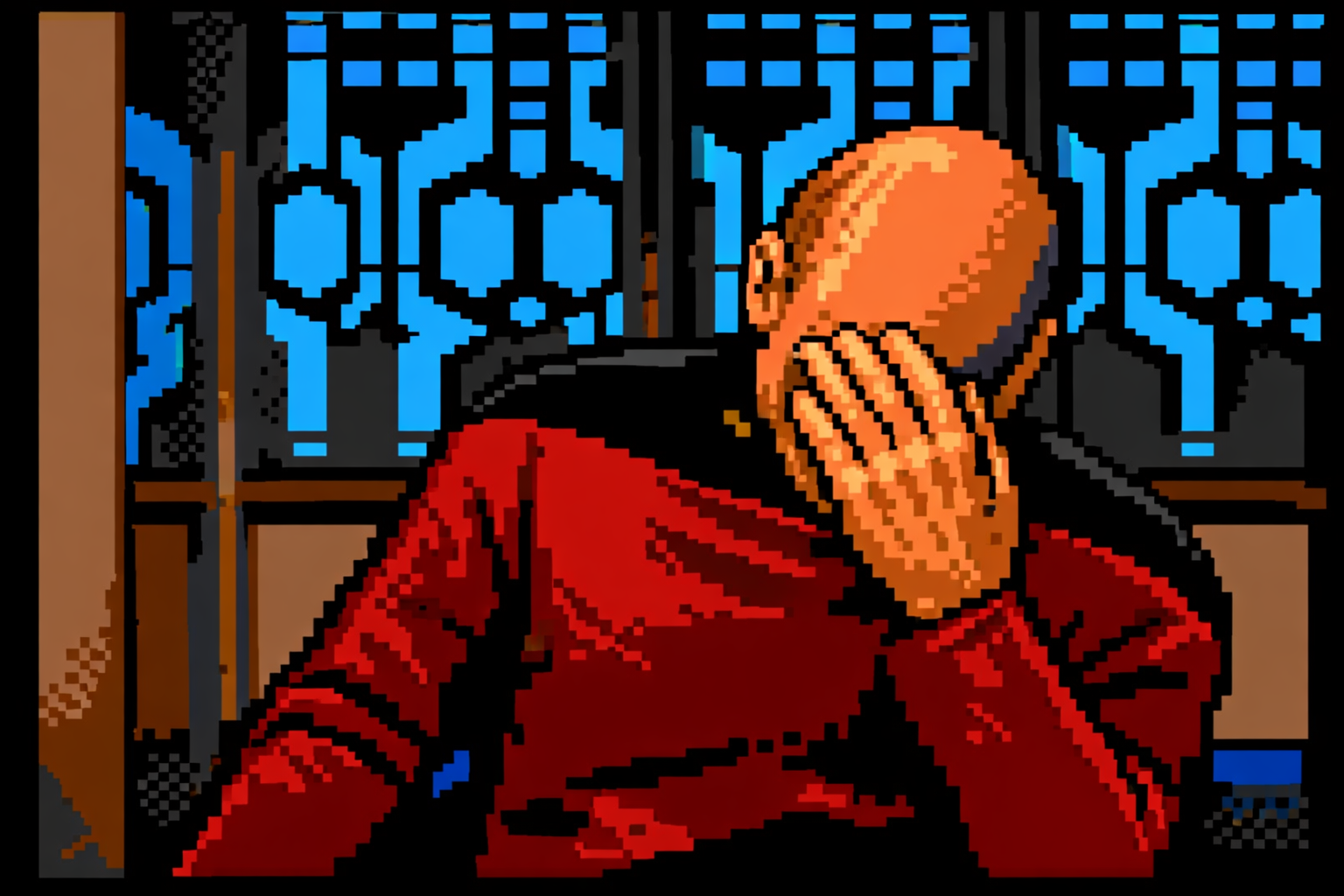

Polling operates inside that reality because opinion moves, turnout shifts, and campaigns react. When a poll misses, it usually misses inside the error bars or because reality moved after the field dates. As Capt. Jean-Luc Picard put it: "It is possible to commit no mistakes and still lose. That is not a weakness. That is life."

Used properly, polling is still a critical tool to inform persuasion, turnout targeting and message testing.

Prediction markets operate in a different universe.

Looking at a prediction market the way you look at a poll is a critical error. Treating the two as interchangeable is like trying to drive while looking through binoculars. You might see one thing very clearly, but you will miss everything else.

At this point it is going to get a little thick, but stick with me. There will not be a math quiz at the end.

While a poll freezes opinion for inspection, a prediction market never sits still. It is a live price that moves as uncertainty, liquidity, time to settlement and opportunity cost all constantly shift. It IS uncertainty being priced in real time. The number on the screen is the going rate for taking on that risk, not a reading of public sentiment.

That is why markets do not tell you what people think. They tell you what traders are willing to put at risk and how much pain they can tolerate if they are wrong. When someone buys a contract at 60 cents, they are not swearing there is a 60 percent chance. They are tying up capital in a position they think is mispriced (which usually means they believe the true odds are higher than the price suggests).

Exposure is the point. That distinction gets lost fast, especially in thin markets.

Why thin markets mislead

In a thin market, size is the enemy. Any serious bet moves the price against you. The mere act of participating distorts the signal you thought you were seeing. That is not the market failing. That is the market doing what markets do. Traders push prices until they find resistance.

In deep markets, that resistance reflects many competing views and real capital on both sides. In those conditions, the price can start to act like a rough, continuously updated forecast because many traders are competing to correct even small errors. In thin markets, equilibrium is reached erratically, often at numbers that look meaningful but are not.

The margin of error in a thin market is not listed in fine print or even knowable. If you want to understand this better, maybe we should look to Jesus.

Will Jesus Return before Jan. 1, 2027?

On Polymarket, the contract "Will Jesus Christ return before 2027?" has recently traded at about three cents, with roughly $24,000 in total volume and a settlement deadline of Dec. 31, 2026. This market will resolve to Yes only if credible evidence of the Second Coming emerges by that date.

That does not mean there is a three percent chance of the Second Coming. It reflects noise, liquidity constraints, incentives and human behavior interacting. That is the residual price of uncertainty.

Some participants would buy "yes" for ideological reasons. Some would trade it as a novelty. Some would misunderstand the instrument. Most rational actors would pile into "no" because they are confident they are right. Long before the settlement date, many of them will try to free up their capital and sell. In that kind of market, the "smart money" should buy Yes at a few cents, not because they believe the event will occur, but because they expect to sell later to someone who wants out of a "no" position.

Three cents here looks a lot more like the margin of error on a survey than a serious estimate of the odds of the Second Coming.

How to Actually Use This Tool

Defenders of these markets will point to big national contests where deep, liquid markets have often tracked results reasonably well. In those rare cases, the textbook story comes closer to true: a large crowd of traders, each with their own information and model, constantly corrects small mispricings. Under those conditions, the price can behave like a rough forecast.

The reality is that most prediction markets in Florida races are not there. It's possible they will get there if the market participation grows. But for now, thin participation means small trades can move prices sharply. That tells you something about market structure, not electoral reality.

Most prediction markets in Florida races are small ponds with a few big fish, not oceans of competing capital. Treating those prices as if they carry the same weight as a presidential market is how smart people talk themselves into bad decisions.

Later on, when early vote totals, absentee returns, turnout signals and calendar pressure begin to matter, markets can possibly absorb information that polls struggle to capture in real time. Even then, price only deserves attention if it comes with real volume and sustained open interest that usually shows up only in big national races or very high-profile fights.

Market movement is not an answer by itself. It is a prompt.

A late move against you does not prove secret information exists. When polls and markets move together, uncertainty is narrowing. When they move apart, averaging them is a mistake. Markets show where uncertainty hurts and how much people are willing to pay to manage that discomfort. The work is figuring out what each tool is picking up that the other is not.

Where this really goes wrong

The problem is that smart people want prediction markets to be magic. They're not. It's just another blunt instrument with sharp edges, built for a specific job. Used correctly, they can keep you honest about risk. Used lazily, they will give you false confidence right up until the votes are counted.

And if you find yourself bragging at a fundraiser about a 60-cent contract instead of knocking doors or checking turnout models, congratulations. The market is about to price in your mistake.

KNOWLEDGE CHECK

In the simplest terms, what does a political poll measure?

💡 HINT: Think about what happens when a pollster calls you on the phone.