FORT LAUDERDALE'S DESIGN PROBLEM

Fort Lauderdale loves a skyline pitch. Big city feel. Iconic design. The next Miami, just with better manners.

The problem? Only taxpayers are footing the bill for ambition. Developers are building boxes, and the city keeps letting them.

Take a drive down 595. Come up from the tunnel. Walk Flagler Village or glance north on U.S. 1. The skyline isn't rising. It's stacking. Wide boxes, skinny boxes, beige, glass, gray. Some are oversized, others have some curved balconies. The latest is a super-thin stick. The city calls it progress. Most residents don't know what it is, but they are starting to talk about the skyline.

It's time to stop hoping that if government builds something bold, the private sector will match it. That theory hasn't worked.

The billion-dollar convention center hotel is the clearest example. It's massive. A 29-story, 801-room Omni project with a waterfront plaza, rooftop views and architectural muscle. The price tag is headed north of $1.2 billion dollars, much of it backed by public funds.

City Hall is next

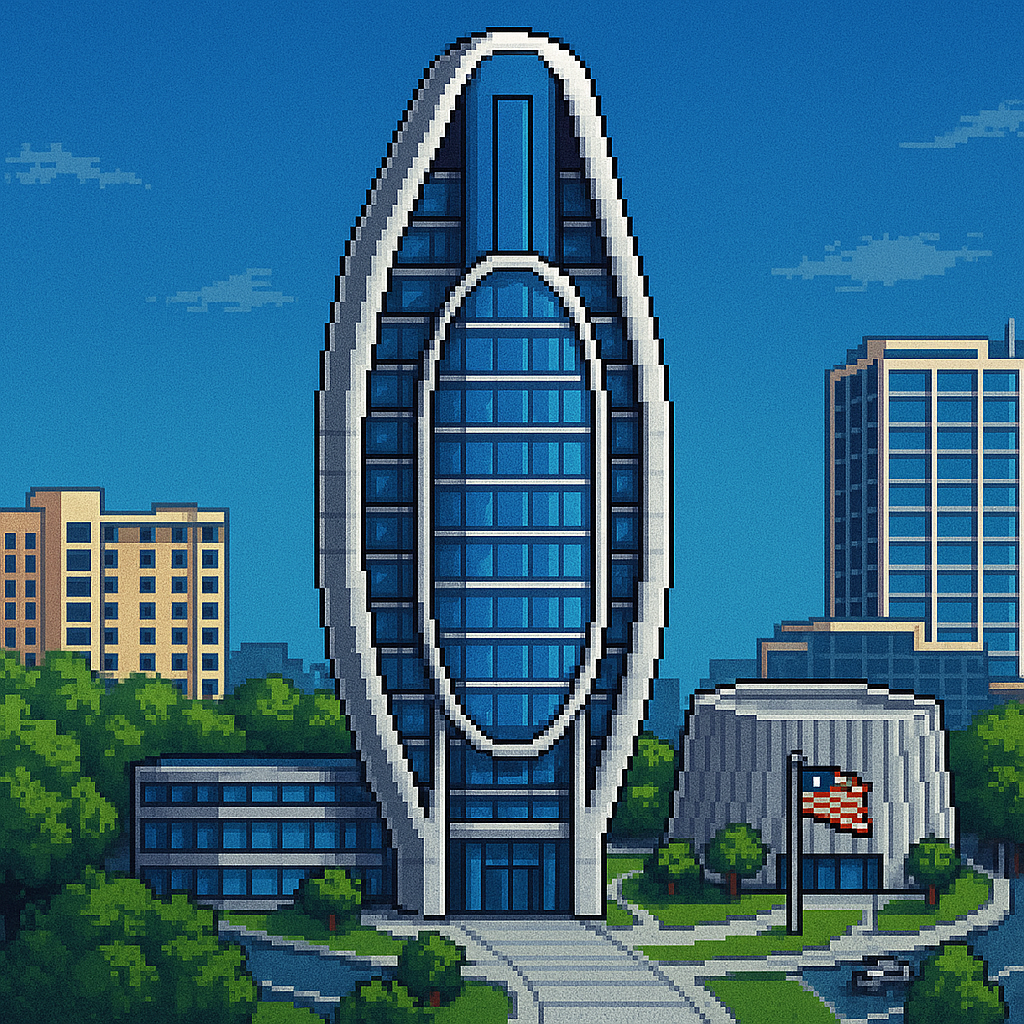

The old 1969 concrete bunker flooded in 2023 and was demolished the next year. Now the city is going all in on a curved-glass design that looks like a ship's hull turned upright. It was the priciest option in a public-private bid process, or around 350 million dollars before the "value engineering" began.

Mayor Dean Trantalis says it's a legacy. Commissioner Ben Sorensen liked it because it didn't look like a rectangle.

But here's the part they don't say.

Commissioner Herbst is right on this point. He has argued that City Hall should be more fiscally responsible and that residents rarely use it anymore. Taxpayers might step inside once or twice a year.

But when they take their children to the museum or the performing arts center, they smell urine and see trash. To them the iconic building does not look like a ship's hull. It looks like a 300-million-dollar middle finger.

While Fort Lauderdale Went Shopping For An Iconic Building, They Ignored The Most Iconic Building Downtown

While the city reviewed glossy renderings, the Broward School Board was openly discussing selling or leasing its downtown headquarters, the infamous "Crystal Palace."

The Kathleen C. Wright building had already been repaired and modernized after Hurricane Wilma. It is a 14 story structurally reinforced iconic government tower in the heart of downtown.

The city likely could have acquired it for about 50 million dollars including renovations and customization. Fort Lauderdale never asked. There was no inquiry, no feasibility review, no coordination.

The closest to public discussion was a throwaway line in a Bosquet article.

Instead of taxpayers paying for a ship's hull, they might have gotten a historic and iconic building for a fraction of the cost.

"Historic and iconic" because it was considered a boondoggle and an albatross for the school board. "Historic and iconic" because the city blew a chance to turn it into a rare win-win-win for taxpayers. "Historic and iconic" because it was the real opportunity to build a legacy by turning a burden into a benefit.

Money for City Hall could have funded schools. The city could have structured a payment plan that gave the school board steady revenue. Taxpayers would have saved on both fronts.

The City Sets the Bar for Itself—and No One Else

What Fort Lauderdale lacks isn't ambition. It's standards.

Developers don't build beautiful things here because they don't have to. There's no serious design review board. No zoning code that demands quality. Just parking ratios and setback rules.

Other cities got tired of ugly. Boca Raton did it through zoning. West Palm Beach embedded form-based codes. Miami has a development review board that sends projects back until they look like they belong.

Fort Lauderdale has none of that. It banks on its own projects to "set the tone." But the private sector isn't listening.

The Punchline

City Hall can call its new tower a ship's hull or a legacy building. It won't matter much.

Most people won't visit it more than once a year. They'll pass it on the way to the library or theater. What they'll remember is that to the average voter, that new glass monument doesn't look like a symbol of pride. It looks like 300 million bucks that could've been used to fix what's broken in their neighborhood or to lower their tax bill.

And they'll see it clearly on their way to the museum.